Infinitesimal transformation

In mathematics, an infinitesimal transformation is a limiting form of small transformation. For example one may talk about an infinitesimal rotation of a rigid body, in three-dimensional space. This is conventionally represented by a 3×3 skew-symmetric matrix A. It is not the matrix of an actual rotation in space; but for small real values of a parameter ε we have

a small rotation, up to quantities of order ε2.

A comprehensive theory of infinitesimal transformations was first given by Sophus Lie. Indeed this was at the heart of his work, on what are now called Lie groups and their accompanying Lie algebras; and the identification of their role in geometry and especially the theory of differential equations. The properties of an abstract Lie algebra are exactly those definitive of infinitesimal transformations, just as the axioms of group theory embody symmetry. The term "Lie algebra" was introduced in 1934 by Hermann Weyl, for what had until then been known as the algebra of infinitesimal transformations of a Lie group.

For example, in the case of infinitesimal rotations, the Lie algebra structure is that provided by the cross product, once a skew-symmetric matrix has been identified with a 3-vector. This amounts to choosing an axis vector for the rotations; the defining Jacobi identity is a well-known property of cross products.

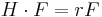

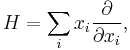

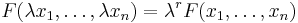

The earliest example of an infinitesimal transformation that may have been recognised as such was in Euler's theorem on homogeneous functions. Here it is stated that a function F of n variables x1, ..., xn that is homogeneous of degree r, satisfies

with

a differential operator. That is, from the property

we can in effect differentiate with respect to λ and then set λ equal to 1. This then becomes a necessary condition on a smooth function F to have the homogeneity property; it is also sufficient (by using Schwartz distributions one can reduce the mathematical analysis considerations here). This setting is typical, in that we have a one-parameter group of scalings operating; and the information is in fact coded in an infinitesimal transformation that is a first-order differential operator.

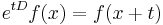

The operator equation

where

is an operator version of Taylor's theorem — and is therefore only valid under caveats about f being an analytic function. Concentrating on the operator part, it shows in effect that D is an infinitesimal transformation, generating translations of the real line via the exponential. In Lie's theory, this is generalised a long way. Any connected Lie group can be built up by means of its infinitesimal generators (a basis for the Lie algebra of the group); with explicit if not always useful information given in the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula.

References

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Lie algebra", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=L/l058370